As we expand the diversity of experiences, identities, and viewpoints represented at “the table,” we may encounter situations that could pose ethical or moral dilemmas.

The collaborative group New Pluralists defines ethical or moral dilemmas as “circumstances that cause us to question whether a person or organization is in ‘good faith’ striving to align with the guiding principles of pluralism.”

What constitutes one of these dilemmas? How do we handle them? Who decides? Thoughtfulness about these tensions is an important step in developing pluralistic settings.

It’s not PACE’s place to “answer” these questions– to be honest, there are usually no universally “right” answers, and most decisions are likely to be inherently subjective and context-specific. But we acknowledge these are legitimate and complicated questions, and you’re not alone if you have them. We have curated some resources from organizations that navigate these dilemmas often, and might provide some insights for your consideration.

This will be an evolving resource list; we will continue to refine and add to it as we learn and engage more deeply in efforts to build social cohesion and pluralism. Have an ethical or moral question you’re trying to navigate? Have a resource that might help address an ethical or moral question? Share it with us at SocialCohesion@PACEfunders.org

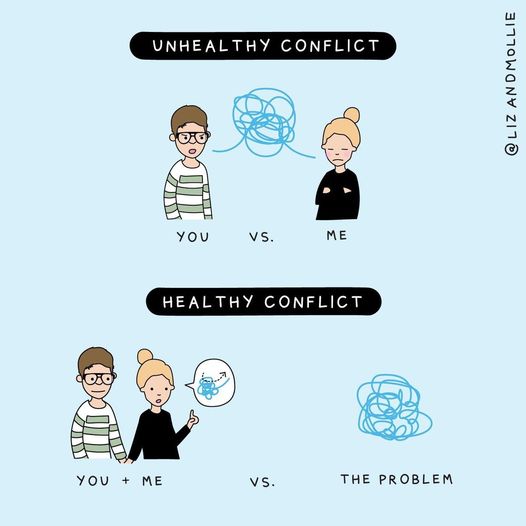

How do we listen to others who express opinions we find deeply wrong or offensive? Remember that interacting or trying to understand is not necessarily the same as endorsing or validating those opinions or beliefs. Science and research show us that engagement can actually reduce prejudice, and that our perceptions about what others believe (and why they believe it) are not necessarily reflective of their actual views. Research shows Americans tend to have a distorted understanding of people who are not like them (including those who are on the “other side” of the political aisle or an issue); More in Common calls this the Perception Gap. Their work demonstrates that while many differences in values between groups do exist, they are often not as extreme or radical as we might think. The group Braver Angels has a set of guidelines for conducting conversations across big divides. They remind us that many bridging and listening efforts are not about dispute-resolution, they are about clarifying what differences exist (and where), and where common ground on priorities may be possible. The Better Arguments project has 5 principles they recommend, among them: “Try to understand why a person holds their belief, rather than having a knee-jerk reaction” to them. There is also the Moral Foundations Theory, which suggests that all human beings share six moral foundations: care, fairness, liberty, loyalty, authority, and sanctity– we just call on them in different ways and different orders of priority in order to form our worldviews and our beliefs about the best way to solve problems. In his book, “Sustaining Democracy: What We Owe to the Other Side,” Robert Talisse suggests we need to understand and consider the reasonable criticism of our positions, in order to form expansive coalitions of allies who share broad goals, which increases the odds of solving problems. In reflecting on this, Daniel Stid writes “Ultimately, we need to engage our opponents not because of what we owe them, but because of what we owe our team members and coalition partners. Only by engaging with reasonable critics on the other side can we ensure we are being sufficiently hospitable to allies who are, or could be, on our [side].” What a social cohesion approach to problem solving suggests is that the “sides” should not be person versus person, but people versus the problem; Adam Grant illustrates this in what he calls “the science of productive conflict.” People may understandably wonder whether bridging differences requires papering over injustices, sacrificing moral values, or accommodating hateful views. Some philosophy suggests that views of justice are often closely tied to our sense of self– so to engage with others who don’t share our commitments can feel like we’re wavering or undermining core convictions; this is one reason it is important to remember to orient conflict toward problems and not people. Constructive Dialogues’ recent paper on bridge-building in the context of systemic inequity and social justice notes that “a large body of research shows that interacting with members of other groups reduces prejudice” and cites several sources of evidence. Their analysis touches on the importance of norm-setting and acknowledging the emotional work and stress that goes into these efforts, especially given it is usually not equal across participants. Try to remember that conflict or disagreement is not inherently bad; high conflict and dehumanization are the problems. “High conflict” is when conflict escalates to a point where it takes on a life of its own and becomes self-perpetuating. To address high conflict, ask a lot of questions and reflect back what you hear, even as you continue to disagree. Amanda Ripley wrote a book called “High Conflict: Why We Get Trapped and How We Get Out” and shares how she has seen people get out of high conflict and she knows it’s possible. “Good conflict” can still be hard and uncomfortable, but is necessary in a democracy… it is how we weigh ideas and solve problems. Amanda says: “To make conflict healthy, people need to have shared goals that they work on side by side, as equals. When they disagree, they have to talk to each other, rather than ignoring each other — or going to war. And it always helps to have snacks. (There are more than 500 studies showing this kind of “intergroup contact” can reduce prejudice and mayhem.)” If we don’t agree on what’s true, can we even have a conversation? Probably; it turns out personal experiences often bridge divides better than facts do. And because ideas of truth can be rooted in concepts of identity and belonging, insisting on what is “true” may actually increase the rigidity of a person’s beliefs. It may seem intuitive that facts are persuasive, but it turns out they might not be very effective in engaging across differences. Research by four professors of psychology, neuroscience, and business ethics found relating personal experiences had more impact on listeners than a set of shared facts. Their study from the National Academy of Sciences examined two different strategies for interactions between opponents: supporting one’s moral beliefs with facts (objective statistics and evidence obtained from reports and articles) versus personal experiences (subjective anecdotes about lived events). It found: “People believe that facts are essential for earning the respect of political adversaries, but our research shows that this belief is wrong. We find that sharing personal experiences about a political issue—especially experiences involving harm—help to foster respect via increased perceptions of rationality. This research provides a straightforward pathway for increasing moral understanding and decreasing political intolerance. These findings also raise questions about how science and society should understand the nature of truth in the era of ‘fake news.’ In moral and political disagreements, everyday people treat subjective experiences as truer than objective facts.” Why is agreement on truth so hard? Philosophy has some answers, and they aren’t just about access to truthful information, but are larger issues of identity and belonging. Further, treating them as matters of “education” can actually increase the rigidity of beliefs and the polarization associated with them. “Psychologist and law professor Dan Kahan and his collaborators have described two phenomena that affect the ways in which people form different beliefs from the same information. The first is called “identity-protective cognition.” This describes how individuals are motivated to adopt the empirical beliefs of groups they identify with in order to signal that they belong. The second is “cultural cognition”: people tend to say that a behavior has a greater risk of harm if they disapprove of the behavior for other reasons – handgun regulation and nuclear waste disposal, for example. These effects are not reduced by intelligence, access to information, or education. Indeed, greater scientific literacy and mathematical ability have been shown to actually increase polarization on scientific issues that have been politicized … Higher [literacy] in these areas appears to boost people’s ability to interpret the available evidence in favor of their preferred conclusions.Beyond these psychological factors, there is another major source of epistemic pluralism. In a society characterized by freedom of conscience and freedom of expression, individuals bear “burdens of judgment,” as the American philosopher John Rawls wrote. Without the government or an official church telling people what to think, we all have to decide for ourselves – and that inevitably leads to a diversity of moral viewpoints.” In his book “The Righteous Mind,” social psychologist Jonathan Haidt suggests two basic questions inform peoples’ reasoning when deciding (consciously or otherwise) if something is true– and they are often not based on logic as much as emotion and desire. The two questions are: CAN I believe it? If so, MUST I believe it? “When we want to believe something, we ask ourselves, “Can I believe it?” Then, we search for supporting evidence, and if we find even a single piece of pseudo-evidence, we can stop thinking. We now have permission to believe. We have justification, in case anyone asks. In contrast, when we don’t want to believe something, we ask ourselves, “Must I believe it?” Then we search for contrary evidence, and if we find a single reason to doubt the claim, we can dismiss it.” What do we do if people are expressing extremist or radical beliefs? Consider counter-messaging and norm-setting approaches; tempting as it may be, banning expression usually doesn’t solve the problem and may make it worse. The extremity of beliefs are not measured by how far away they are from our own beliefs, values, or opinions; “extreme beliefs” are different than widespread or even vehement disagreement. The National Institute of Health explains that extreme beliefs tend to be ones that are overvalued in a person’s cultural, religious, or subcultural group and carry an intense emotional commitment (they are rigid and non-delusional and are different than obsessions). Extreme overvalued beliefs are a predominant motive for violence and terrorism worldwide. As much as we may like to quash the dissemination of extremist beliefs (especially to prevent their normalization), the NIH research shows that if expression of those ideas is repressed in one arena, they will likely pop up in another. For example, banning the use of extreme websites may in fact worsen the behavior—users migrate to other, more secret websites, and the extreme ideas begin to carry even more valence. Instead, balancing the extreme content with alternative content may be a more effective strategy. Moonshot uses data-proven techniques to respond to online harms. One example of their work is Counter-Messaging– connecting individuals attracted to harmful content with compelling and credible alternative messages across mainstream AND difficult-to-access platforms. Over Zero uses neuroscience, psychology, and sociology to understand the roots of conflict and identity-based hate. Their resources explain the core concepts of what drives extreme division, and they have tools to help counterbalance it through narrative, communication, and norm-setting that turns down the temperature for violence and builds community resilience to violence over time. Does not banning extremist beliefs mean we’re normalizing or legitimizing them? Some experience suggests listening and trying to understand people with extremist views may lead them to evolve their beliefs. The Computational Neuroscience Research Group performed research to understand how opinions change; they found that extremism often emerges in locations with limited communication and access to external information. Although networking extremists with new individuals has the potential to spread radicalization, it also increases the probability that extremists will find a bridge to more moderate attitudes that, over time, persuades them to soften their extreme beliefs. Consider the lived experience of Daryl Davis, an African American who has engaged with members of the Ku Klux Klan, and convinced a number of members to leave and denounce the group and ideology. He says his experience has taught him that exposure is what reduces fear and, with nothing to fear, there is nothing to hate. What about “Bad Faith Actors?” How do we know when someone is operating in bad faith? Keep in mind, a “Bad Faith Actor” is not someone with whom you vehemently disagree, even if you cannot understand or see merit in their belief or idea. A Bad Faith Actor is someone who is engaging with the intent to promote a hidden, unrevealed agenda—often to dominate or coerce the other individual into compliance or acquiescence of some sort. They often lack basic respect for the rights, dignity, or autonomy of the other party; a person engaged in bad faith does not accept the other person as s/he is, but demands that s/he change in order to satisfy his/her requirements or to accept his/her will. New Pluralists offers some signals that someone may not be operating in good faith: This resource page was curated and drafted by Kristen Cambell with support from Betsy Rider. It was last updated: April 5, 2023

Another example is Megan Phelps Roper, who grew up in Westboro Baptist Church. She chose a path away from those extreme beliefs because of open-hearted exchanges she had with people (on Twitter) who listened to her assertions and kept asking questions. Answering the questions posed by people who were trying to understand her (rather than condemn her) enabled her to reflect on the validity of what she’d been taught to believe and recognize the problems and harm associated with her upbringing. She left Westboro and became an advocate for the people she was once taught to hate. As Roper says, “We have to talk and listen to people who disagree with us. It’s hard because it means extending empathy and compassion to people who show us hostility and contempt. The impulse to respond in-kind is so tempting.”